I’ve attempted a semi-unified theory of James Franco for the London Review of Books. You can read the first paragraph here, register for free to read the whole thing here, and check out a couple key paragraphs below:

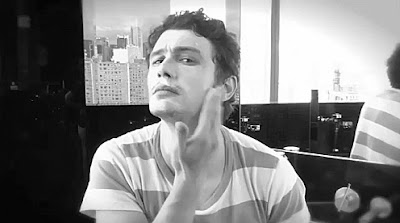

Acting with James Franco and Erased James Franco didn’t shift public perception of the actor much: the former was a lark and the latter shown only in museums (there are a few minutes on YouTube; they’re enough). But in 2009, Franco embarked on a more public project. While discussing a new film with Carter, in which he was set to play a former soap opera star who has retired because of mental illness, Franco thought that it might be fun to star in a soap himself. He proposed the idea to the producers of General Hospital, America’s third-longest-running television drama, and the oldest still on air. Franco wanted his character to be both crazy and an artist. They created ‘Franco’, a one-named, pseudonymous graffiti artist who now sells crime-scene re-creations in galleries for good money. Shades of Banksy – though ‘Franco’ is actually a deranged killer who is terrorising the fictional town where General Hospital is set. Franco persuaded the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles to let them film there. In that episode, ‘Franco’ has a one-man show (‘Francophrenia’) at MOCA, and a detective – who has formed an unlikely partnership with a mob killer in order to track ‘Franco’ down – shows up to arrest him. In the climactic showdown, ‘Franco’ falls to his death from a third-storey balcony in the museum, while Kalup Linzy, an artist who draws on soap opera iconography in his own video installations, performs a musical number.Read the rest. (Pictured: Franco channeling Bruce Nauman.)

Franco has said that this piece of ‘performance art’ (his own description) was intended to make people ‘ask themselves if soap operas are really that far from entertainment that is considered critically legitimate’. The episodes are full of half-baked dialogue on aesthetics. In one, ‘Franco’, eyebrow arched, asks a magazine editor how she knows something is a work of art. ‘Everyone says so,’ she tells him. ‘Then it must be,’ he replies. These exchanges fall with a thud. What is interesting about the endeavour is what it says about Franco as an actor and as a celebrity, and what it might suggest about the nature of celebrity, now, for actors. ‘I disrupted the audience’s suspension of disbelief,’ Franco wrote in a piece about the project for the Wall Street Journal, ‘because no matter how far I got into the character, I was going to be perceived as something that doesn’t belong to the incredibly stylised world of soap operas. Everyone watching would see an actor they recognised, a real person in a made-up world.’ The phrase ‘real person’ jumps out here. His General Hospital castmates are real people, too. Franco means that people watching the show know who he is. But people watching movies always recognise the stars. Once upon a time, that recognition would not have made them seem ‘real’, but grand – maybe even, in the case of someone like James Dean, mythic. Franco’s ‘star power’ is remarkably diminished: he jumps out from his surroundings because of their littleness. ‘Franco’ is ‘mysterious’, but Franco is not.